The treaties and laws governing how drugs are regulated by nations were, for the most part, written a half-century or more ago. And while the science surrounding drugs and drug use has advanced rapidly over that time, the laws have barely evolved.

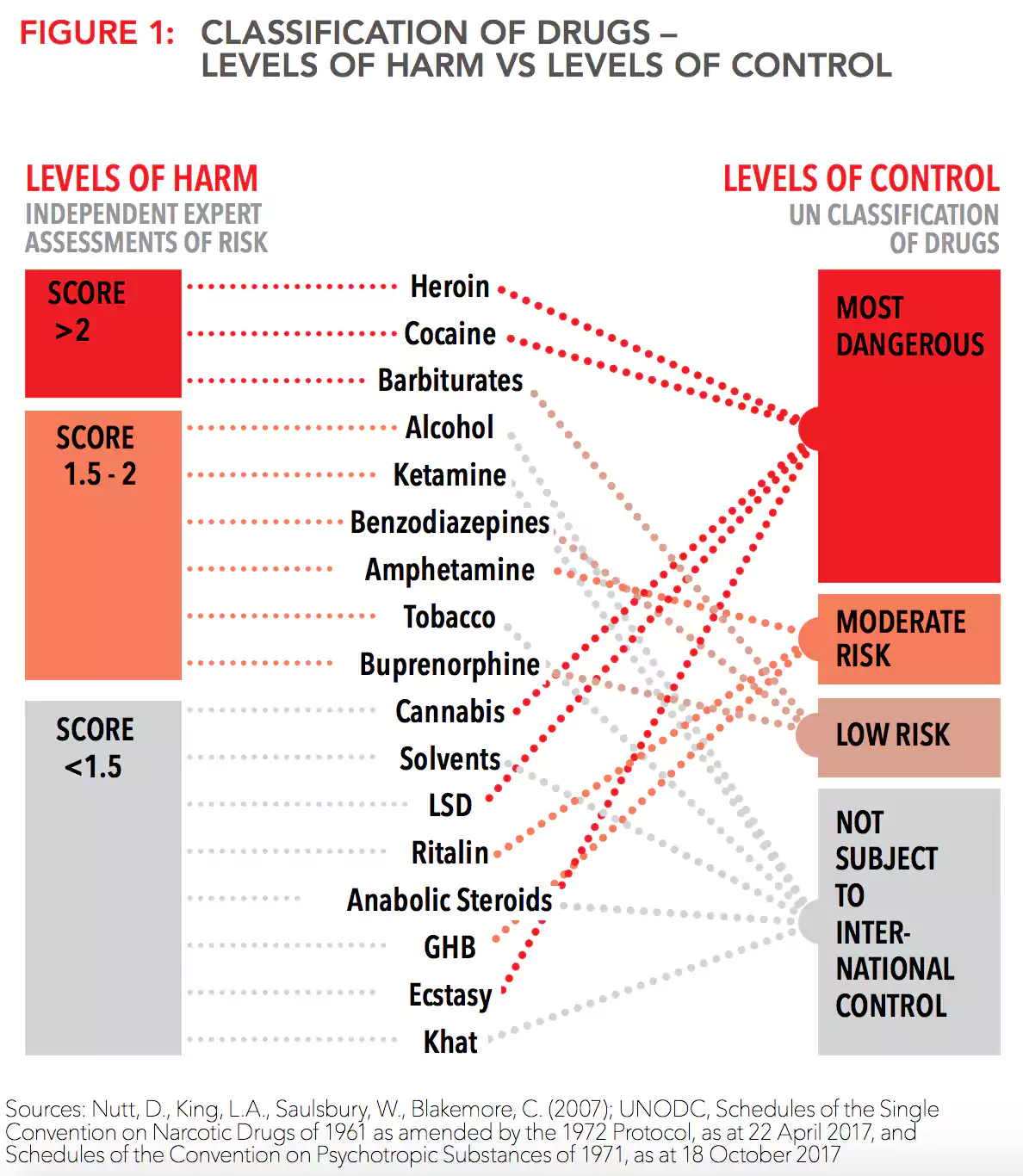

As a result, there is little correlation between the dangers of various drugs and the stringency of laws regulating their use. That disconnect is abundantly clear in the diagram below, which comes from a new report on world drug use by the Global Commission on Drug Policy, a group that advocates for less-punitive drug laws.

In a 2007 Lancet study, drug policy experts assessed the potential harmsassociated with using various drugs, using the latest available research to come up with a total measure of “risk” for each drug.

Cannabis (marijuana), for instance, is a relatively low-risk drug: There's no chance of overdose, and rates of addiction are relatively low. Heroin, on the other hand, is extremely dangerous: deadly in high doses and very addictive, to say nothing of the dangers posed by potential adulterantsthat dealers and traffickers often add to their products.

In a purely rational world, you'd probably regulate cannabis and heroin very differently: One is quite deadly and damaging, the other much less so. But under international law, as set by the 1961 U.N. Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, the two substances are for all intents and purposes equivalent: They fall under the strictest category of regulation, reserved for substances with no medical use and a high potential for abuse.

The U.N. Single Convention sets the terms for how countries regulate drugs within their borders. Generally speaking, the countries that are party to it — nearly every country in the world — abide by it. If the treaty says that cannabis and heroin are equivalent drugs, that becomes the de facto position of most of the world's governments — regardless of what the science says.

Here in the United States, for instance, the Drug Enforcement Administration didn't officially acknowledge until 2015 that marijuana is less dangerous than heroin (the drugs do, however, remain classified the same under federal law).

On the other hand, alcohol and tobacco are much deadlier substances than we usually acknowledge. Excessive drinking kills upward of 88,000 people in the United States each year, while tobacco is implicated in nearly half a million fatalities — most because of long-term health issues — each year.

Both substances are highly addictive, alcohol use is closely associated with violent crime, and some research indicates that both substances may serve as “gateways” to more lethal drugs, such as heroin. But neither alcohol nor tobacco are regulated under international drug treaties. They remain legal to purchase and consume in most countries, subject to modest restrictions, such as age limits, depending on locale.

In recent years, certain places have started updating their laws to restore a sense of proportionality to the way they regulate drugs. In 2012, for instance, Bolivia withdrew from the U.N. drug treaty to lessen restrictions on coca leaf — a traditional stimulant that also happens to be the raw material for making cocaine. The rejoined the treaty in 2013, claiming an exception for coca leaf chewing.

In Uruguay, as well as in a number of U.S. states, marijuana is legal for recreational use. Such moves have prompted some saber-rattling from the United Nations but nothing in the way of serious repercussions.

As of 2016, according to the Global Commission on Drug Policy report, roughly a quarter of a billion people worldwide used drugs that were illegal. Nearly 90 percent of them did so without experiencing addiction or diagnosable problems related to their drug use.

Author: Christopher Ingraham

January 9, 2018

The Washington Post